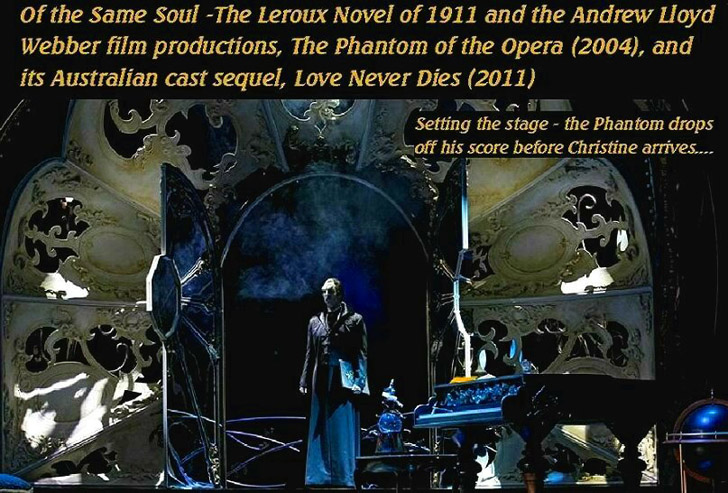

Of the Same Soul …

“Christine, you must love me!”

And Christine's voice, infinitely sad and trembling, as though accompanied

by tears, replied: “How can you talk like that? When I sing only for you! ”

How these words still ring with feverish excitement.... Outside her Paris Opera House dressing room, Raoul was listening to Christine and, unbeknownst to him at the time, the Phantom. This dialogue from chapter two, The New Margarita, of The Phantom of the Opera novel of 1911 by Gaston Leroux, is one of the underlying keys to understanding the tempestuous trilogy of tales woven about the Phantom and Christine Daaé. It's obvious from her reply to the Phantom that without a shadow of doubt, at that moment, she does love him.

Throughout the novel, while he strives to bend her will to him as her future lover, and her voice to him as the present teacher known to her as the Angel of Music, and she tames the tiger carefully and reverently, both are swept away by an irrevocable love. As do diamond-crested waves that crash and retreat and crash again upon a shoreline, so has their story unfolded like a faithful tide. Over a century since the book was opened to its first page, over decades of filmed versions, with their love story still set in the early 1900s, the couple finally finds resolution in a 21st century film an ocean away from Paris in new haunts – the Phantom's Coney Island amusement park known as Phantasma, the bedazzling gem he created and found solace in during the years without Christine.

|

Home Page |

|

|

|

Spring 2014 |

|

|

|

|

From first frame to finale, the latest chapter of love between the Phantom and Christine is eye opening and life changing. In the finest tradition of a melodramatic morality play of Love, it defines what is really beautiful, and how Love can withstand all but will not necessarily win at any cost. In that light, the 2011 Andrew Lloyd Webber filmed stage production Love Never Dies (LND) may well stand forever as the perfect sequel to the composer's 2004 film, The Phantom of the Opera (TPOTO) and Gaston Leroux's original Gothic romance, The Phantom of the Opera.

Set a number of years after the original novel, LND represents an evolution simultaneously of the classic novel and previous film and stage productions, continuing the love story of the Phantom and his one true love, Christine Daaé, while faithfully bringing Gaston Leroux's glorious characters and settings back to life with an elegance of mood and trappings. What LND avoids, as it's most concerned with the high romance of the love story, is Grand Guignol theatrics and sprees of vengeance. After all, the Phantom has had to “behave” himself in Coney Island so as not to draw attention to his real identity and reputation earned in Paris a decade earlier.

It is quite fitting that LND was filmed in the 100th year anniversary of TPOTO published in novel form in North America, and the Phantom in all his incarnations is still highly popular today. On social media for example, the official facebook Love Never Dies site has over 94, 700 “likes” at this time of writing. It's no surprise that an original first American printing of Leroux's novel is currently being offered by one book dealer for $38,500 US.

LND as a grand and thrilling love story also captures many of the darker workings of the novel, even with the Coney Island setting. The earlier serialization of the book was quite popular; although the novel itself received less attention in 1911. It wasn't until it landed in the hands and under the eyes of the movie industry in the 1920s that the Phantom sprang to life on the screen and came into demand in print. From that point, with make-up created by Lon Chaney Sr. in 1925, the Phantom became characterized as a grotesque monster.

For its time the novel was daring and risque, not unlike the earlier Bram Stoker Gothic novel, Dracula. Phantom's undercurrents of greed, immorality, deceit, and sexuality and murder for the time were scandalous. And still are. Yet it was a hand in glove fit in an era when so much mysticism and “art for art's sake” were infiltrating mainstream society. The time was one of unleashing creativity, of experimenting and tasting, of freeing new thoughts and abandoning long held mores and beliefs. “Stars” on the stage and in the early cinema gaining followings marked the beginning of “pop culture” which continues to this day. The Phantom mask itself, immediately recognizable in its many conceptions since the 1920s, is an iconic image that will likely still haunt us one hundred years from now.

Topping the list of personalities in the news internationally around the time Leroux wrote The Phantom of the Opera was magician Harry Houdini – who interestingly was born with the name of Erik, the same name given to the Phantom by the author. Leroux's wicked underworld back then was in stride with wars and intrigues, criminals and murderers like Jack the Ripper, the Victorian street life found in Charles Dickens novels, and post-Victorian parks which at night became the shadowy havens of society's lowest dregs. Street corners and backrooms belonged to often obscene sideshows and freak shows, magicians and carnies, Gypsy caravans and Bohemians, and relatively unknown artists like Picasso who in the early 1900s were selling their paintings for bread. The air hung heavy with hemp and opium, cafes were dizzy with absinthe, as wine and song spilled into the streets.

In contrast, the arts reigned over that underbelly, with grandiose architecture on the scale of Paris and other European opera houses and museums, inventions that would shape our world to come, dazzling big-top circuses, musicians and experimental compositions, idealistic poets, celebrated artists and their salons, and writers who had created Dracula and Sherlock Holmes. Such was the contemporary world that helped birth life and personality to the Phantom of Leroux's novel, with the author stable upon one foot in the conventional sense and sensibility Victorian world, and flying with the other in the burgeoning sense and sensuality realms of the Art Nouveau and L'Art de Vivre movements.

LND has all the contexture Leroux might have utilized to write a similar sequel a century later. In the same vein, many bits and pieces of the novel have been picked up and incorporated into the 2011 filmed production. What appears to be the largest departure from the novel, the transplanting of the Phantom from Paris to Coney Island, is actually a natural transition. Erik, as recalled, because of his deformity was once a sideshow attraction and likely spent much of his youth in a circus fair in Nijni-Novgorod in Russia. In fact, a few of the starry backdrops resemble Russian skylines with orthodox buildings and circus features.

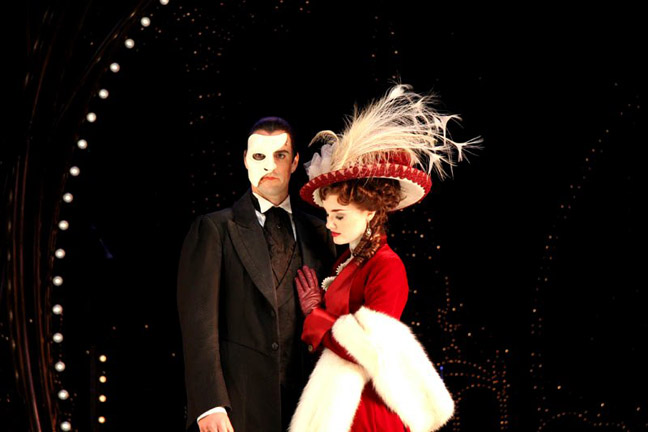

In costume for Love Never Dies, Ben Lewis as the Phantom, and Anna O'Byrne as Christine shortly after her arrival from Paris. A publicity photo taken of the leads, although not a scene from the musical or filmed production.

(Photo: Matt Edwards)

Freak shows were sadly a standard in many circus venues back then. Today one looks differently and rightly so at deformity, with every effort made to accommodate and integrate all people as fully as possible into regular society. At the turn of the century, however, it wasn't uncommon to find unfortunate souls hidden away at home or institutionalized, or resigned to join a circus to be ridiculed for monetary gain and treated by spectators without dignity or respect. While imprisoned there in his youth, Leroux had his Erik become a vocal artiste and an expert of magic, receiving his education from Gypsies.

According to the Persian character in the novel, Erik “...sang as nobody on this earth had ever sung before; he practised ventriloquism and gave displays of legerdemain so extraordinary that the caravans returning to Asia talked about it....” His reputation grew so great in Persia that his escape was arranged, and he soon moved in the Royal Court there at will, advising on architecture and devising methods for the ruler to disappear at will in his own palace. His escape had to be arranged once again by his Persian friend, as the ruler worried that Erik's knowledge of the tricks of the palace would be revealed.

Erik and the Persian then moved on to Turkey and found favour in the Turkish Court in Constantinople, where he invented secret rooms, lock-boxes, and even automata – and a particular automaton that could impersonate the Sultan as necessary when the ruler was elsewhere. Knowing and having created too many secrets of defense for the Turkish Court, he moved on this time to Paris. Somewhere along the way he had even picked up the talent of mimicking the calls of wild animals and insects, such as lions and leopards or a tse-tse fly by manipulating one long resined string upon a tabour or timbrel – with which he would one day terrify captives to the point of madness in his “room of mirrors.”

Now a wealthy man, Erik bid on the construction of the Paris Opera foundation – which was accepted – and which gave him entry and opportunity to create his own lair, and secret passages, rooms, and trap doors for his own use. And thus, because of his genius, and his hideousness through no fault of his own, and the unexpected situation of his falling in love with someone he first thought of as unattainable but teachable as he recognized a talent perhaps as great as his own creative force, he became The Phantom of the Opera, also known as “O.G.” or Opera Ghost.

Mechanical contraptions and other creations of the Phantom's continue to be seen in LND, including a regal horseless carriage, the musical toy given to Gustave, the mirror and the hidden wall passage in Christine's dressing room, and spectacular tall gleaming revolving crowned pyramids that housed golden souls rejected by society in The Beauty Underneath sequence.

Leroux in his novel relates about the Phantom that “...he had to hide his genius or use it to play tricks with, when, with an ordinary face he would have been one of the most distinguished of mankind! He had a heart that could have held the empire of the world....” So, this highly intelligent man who was capable of great love, who had been long denied acknowledgment by the world of his talent and tender feelings, was damaged in every sense of the word. Undoubtedly his thought processes and behaviour had been warped, causing him to lash out murderously against real or imagined threats. (Yet we know there remained a tiny corner of his heart that was possessed and protected by True Love.) If such had occurred now in this century, would the Phantom ever be brought to justice by the court or by public appeal or opinion? Would he have been committed to an institution? Who knows?

LND in many ways gives the Phantom back his humanity, his right to love and be loved, the way he is. Although in most films and some plays, Christine does not wear the Phantom's gold ring of the novel– and it was a wedding ring – by the end you realize that there has never been any greater love story. Ever. It all fits together in the head and the heart.

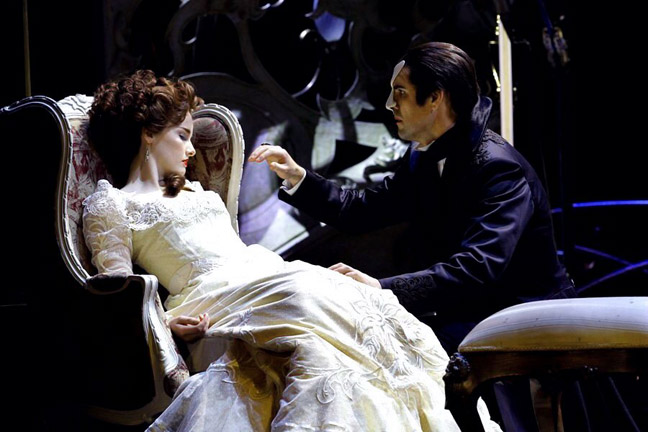

The point of view is also unique in the respect that it is not one-sided as to male or female, but encompasses the sentiments and quest for love by both leads. This imparts a greater genuineness and zest to the love story, and it shows in the performances. It is not the traditional sentimental fable where a strong male dominates a meek female; the LND romantic leads are equals in spirit, will, and fair play. Upon their reunion in the hotel suite, Christine faints at the sight of the Phantom after ten years of separation – and then upon waking, after a gasp, the very first thing she does is yell at him, reprimanding him resolutely in song. Then begins the dance of two for her, of part resistance and part succumbing, that will culminate in the decision during her Love Never Dies aria of whom she really loves. Anna O'Byrne and Ben Lewis' dedication to bringing out a phenomenal authenticity to these well-rounded characters is reinforced by the sense that they also trust each other completely as professionals. Onstage, theirs is a perfect waltz within the storyline, heart to heart and talent to talent.

The beginning of their reunion in a Coney Island hotel suite. After fainting, Christine was carried to a chair by the Phantom. The grand love duet, Beneath a Moonless Sky, will soon ensue.... (Photo: Jeff Busby)

The love triangle really comes to the fore in LND. A temperamental Raoul (played with sharp knack and effervescence by Simon Gleeson), the Vicomte de Chagny, is still deeply in love with Christine, now his legal wife. As in the other parts of the trilogy, he continues to bear a jealousy and mutual hatred toward the Phantom, as well as a sarcasm toward Christine found specifically in and throughout the novel. Raoul had also likely never forgotten, according to Leroux, that he once was certain that Christine loved the Phantom in a way that she would never love him. Even after she proclaims her love for Raoul, she again feels a captive of the Phantom. Her this way-that way feelings are a savage tango that left Raoul uncertain about their having any future at all; they had only ever kissed like brother and sister by that point.

With that kind of unsureness plaguing his thoughts, by the time LND resumes their story, the years had seen Raoul spiral downward into alcoholism and financial ruin, with his only respectability and income now derived from Christine, who had become a successful opera singer and was in demand by such impresarios as Oscar Hammerstein. Although the press and onlookers taunt him about his gambling upon the de Chagny family's arrival from Paris, Raoul thinks of himself as being a good husband and father. But is he really the matchmaker's ideal choice for Christine?

Much romance can be found in the bestowal of a single flower. The 2004 film has Madame Giry present, on behalf of the Phantom to Christine, a single beautiful red rose saying, “He is pleased with you.” Raoul appears soon after with a spur of the moment “borrowed” bouquet of flowers, having plucked them as an afterthought from the opera house managers to present them to Christine in her dressing room.

The Phantom and Christine in her dressing room after her performance at the Phantasma concert hall, a rose upon the table, and a note from Raoul. (Photo: Jeff Busby)

Regarding roses more closely in the novel, Madame Giry revealed to a police inspector and opera managers that the Phantom had a woman with him at times when he attended performances, a woman to whom he always gave flowers, or a single red rose for her bodice, which sometimes was left behind. Giry was always asked to bring a footstool to the Phantom's grand tier Opera Box 5, presumably for the woman. On one occasion, a ladies fan had also been forgotten. This led the inspector to inquire if the Phantom was married. Or had Christine been involved with the Phantom earlier than the three months anyone had suspected? Or was there another woman, one of the “women” the Phantom boasted of to Christine? “When a woman has seen me, as you have, she belongs to me. She loves me forever. I am a kind of Don Juan, you know!” he ranted in a frenzy comparing himself to the virile hero in his opera, Don Juan Triumphant, after being unmasked by her. (Erik had only declared that he had been denied “the joys of the flesh” in the 2004 film.)

Forward on to roses in LND, when Raoul comes to Christine's dressing room before her aria, she remarks “how you look like that handsome young boy in the opera box – the one who used to toss me a single red rose,” and he doesn't acknowledge in any way that he had thrown a rose. After performing her aria and choosing her true love – the Phantom who is now with her – she first sees and picks up a single red rose from the centre of the table and looks to the Phantom, then quickly puts down the rose to pick up a note Raoul had placed near it. The suggestions are so subtle in LND about the rose; the phantom is not distressed by it so he must have left it, but he does grow concerned as Christine begins to read the letter. The two become alarmed then as to the whereabouts of their son, Gustave.

The roles of the Girys, mother and daughter, have been expanded credibly in LND; after all, singer and dancer Madame Giry had always been the Phantom's benefactor and overseer of sorts. Daughter Meg Giry in the sequel is given up to the immorality of the times and harbours a deleterious obsession with the Phantom. She was only curious about the Phantom originally as a young girl, but in LND she is a young woman enraptured by him – “Mother, was he watching?” Throughout the sequel, Meg uncoils like an unpredictable wound-tight watch spring, bit by bit, as her love for the Phantom is always hopeful but never requited.

During the tense moments of the last scene, the fully human Phantom immediately recognizes from where Meg's reactions have originated, as he himself had experienced similar pain, abuse and rejection. When she then becomes totally unhinged at the mention of Christine's name by the Phantom, the tension mounts to a frightful height and becomes shocking beyond belief...much in the same way the Phantom in the novel lost touch momentarily with reality and had planned a wedding murder-suicide with Christine. (Even then, his love for Christine eventually prevented him from harming her, and he released her to find love and a future with Raoul.)

The saddest aspect of the LND climax is that Christine is shot by Meg totally by accident. The Phantom's own hands were grasping Meg's wrists when the gun misfired, as he tried to loosen it from her grip when she appeared intent upon committing suicide. All hope for normalcy and true joy that he thought he had gained once knowing Christine was truly his was now shattered. To lose her at this point, the woman he had always considered as his wife, is an agonizing twist. The Phantom's heart had already once been broken and mended; now it was definitely in a thousand pieces.

It's a heart wrenching ending for an audience to accept, with a kindred sense of tragic loss to the Victorian romance, Wuthering Heights. In the depths of sorrow, the Phantom pulls himself up slowly along the railed walkway. The whole brief lifetime of that one day, of love in full bloom with Christine belonging only to him, was sealed now in his memory forever, and with his spirit wounded and failing, he sinks to his knees as upon an abyss of woe. To read his thoughts during this denouement, what would they have been? Of love and then of music? Conceivably that she could never come to him again, and that never again would he hear the sweetness of her voice reaching rapturous perfection for him alone....

Their real world had once been “swept away” by love in a duet earlier on, but now that other opulent world where their love and music had called out its joy while they lived within its perpetual dream, had vanished as quickly as mist touched by sunlight. In the eternal fragility of things, their future had been taken away. Again. There would be no second chance this time. But then, suddenly, he realized that another facet of Christine's love did remain with him He tremulously and softly sings her words to their son. Gustave no longer fearful of his Phantom father, with one gentle touch of his hand upon his unsure cheek so unaccustomed to receiving genuine affection, confirms that her love still remains for them both. One is not ashamed to cry openly at that moment. Thankfully the Phantom had their son, Gustave, the one tangible remaining proof of his and Christine's true love for each other. These scenes cement how brilliant an actor Ben Lewis truly is.

As to the existence of Gustave, it is no surprise that the Phantom and Christine had a son, who figures prominently in LND. In the original novel narrative, the Phantom referred on more than one occasion to Christine as his wife. The Phantom says to the Persian and also referring to Raoul, “You are now saved, both of you. And soon I shall take you up to the surface of the earth, to please my wife.” (The italics are Leroux's.) A little further on, the author continues with the narrative, “The Persian still had in his ears the natural tone” in which the Phantom had said “to please my wife” and also “advised him to not speak to 'his wife' again.”

Indeed, at that point in the novel, Christine is in his lair and his company, demure, submissive and “wifely” in her behaviour toward the Phantom and his guest-prisoners. It could have been minutes, days or hours that passed between the rescue of Raoul and the Persian from the mirrored room and lower trap-doored section and the time they awoke in the Phantom's rooms. If days, anything could have happened between the Phantom and Christine.... With the Phantom viewing themselves as, and behaving much as a married couple would, there would be every possibility of a child imminently appearing in Christine's life. LND drew those threads closer together wonderfully, creating the wholly believable tableau of their having a son.

On the other hand, also in the novel, in the face of full reality the Phantom finally decided to release Christine after her tears had mingled with his beneath his mask and he had tasted them in his mouth, perhaps feeling in her tears that her love for Raoul was greater than her affection for and fear of himself. But Leroux, through half-suggestions, turns in plot, of opening and closing doors incompletely and unsatisfying the reader, leaves it all open again to further scrutiny – and maybe a second sequel? As the very last line of the novel's epilogue reads, "It is no ordinary skeleton."

How the Leroux novel ends reveals the Phantom's romantic side unto death, where he had requested that Christine return his ring to him after his passing – and is it at that place where she came to find “where he hid” in the Beneath a Moonless Sky duet in LND? Perhaps. Wrote Leroux about the last of the Phantom, “The skeleton was lying near the little well, in the place where The Angel of Music first held Christine Daaé fainting in his trembling arms, on the night he carried her down to the cellars of the Opera House.” Clearly, he had died of a broken heart.

Love Never Dies succeeds magnificently in tying everything together from all its predecessor Phantoms, by turning tragedy into triumph. It is seamless in the storytelling, and its theme is familiar and close to the heart at the same time that it is universal – most everyone in the world has lost someone they once loved. And love does hurt. We are given too little time to share all the truths of Love. To see a character such as the Phantom suffer so with a soft and tender heart of flesh hits home. It's a given that love is one remedy that brings hope – that in some form, love will survive. As the Love Never Dies aria exquisitely proclaimed, sung gloriously by Anna O'Byrne: “Love lives on....” All the Phantom will ever have to do is glance down, hesitantly, and then tenderly, into his hands, to see that “other world” of love – the one that will always remain between himself and Christine.

|top|